User Manual: GenerationOne FSDK

1. Introduction

This manual is intended as an introduction to the GenerationOne Flight Software Development Kit (FSDK). The GenerationOne FSDK is a software framework, library and tool set for the creation of spacecraft onboard software.

1.1. How this Manual is Structured

We have tried to structure this manual to allow it to be used as a reference whilst you are learning to use the FSDK. The first three chapters after the preamble introduce the general concepts and principles behind the GenerationOne FSDK and describe how to install and set up the software on your development workstation. As part of this introduction we describe an example, supplied with the software, which you can compile and use on your workstation immediately after installation.

In the following three chapters we present a practical guide to creating onboard software in the form of tutorials and a reference.

-

Section 6 (Working with a Deployment) describes how to create onboard software from existing software components included as part of the FSDK;

-

Section 7 (Working with a Component) provides a reference for the different parts of a component as well as how that integrates with a deployment;

-

Section 8 (Components tutorial) describes how to create a software component of your own and add it to a deployment.

Note that the tutorial material in Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8 is being replaced by new HTML tutorials. These may be found under Documentation/Tutorials.

The following (Section 9) presents a more detailed guide to TMTC Lab, the graphical software environment which can be used as the “ground” when developing and testing the onboard software.

Finally, the remaining chapters detail the support that the FSDK offers for different operating systems (such as POSIX and FreeRTOS) and different platforms (such as Linux, the Clyde Space OBC and the GOMspace Nanomind). An example is supplied for each supported platform, and the chapter on that platform describes the example.

1.2. How to Use this Manual

There is a wealth of material in this manual, and each reader will have different preferences around how to get the most value from it. For a new FSDK user, we recommend the following order:

-

If you plan on working within the FSDK virtual machine, set it up on your host machine as described in Section 4.1.

-

If you would rather work with the FSDK installed natively on your machine, carry out the FSDK setup steps in Section 3.

-

Proceed to the new HTML tutorials. These are not part of this document, but may be found in the FSDK directory under

Documentation/Tutorials. -

Section 2 will then revisit the topics of those tutorials in a more general setting. It will also introduce more features of the FSDK, and discuss some of the structural features of GenerationOne flight software.

-

Next, the latest iteration of the User Manual tutorials may be of interest. These are found in Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8 and cover more material, but in less detail, than the new HTML tutorials.

-

Finally, to apply your new knowledge to other platforms, refer to the relevant platform and operating specific chapters towards the end of this manual.

2. Overview

The Bright Ascension GenerationOne FSDK has been designed specifically to make the development, or modification, of onboard software faster and easier to validate. To achieve this we have based the software on components each of which has a regular interface. Components can be added and removed easily and help encapsulate the code which provides the key functions of the onboard software in a form which is amenable to intensive unit testing. The library of components supplied with the FSDK covers most of the typical functions that onboard software is required to perform; also included are a set of components to permit interfacing to common hardware.

This chapter gives an overview of the onboard software and the design principles we have followed. The information presented here should help you to understand the general layout of the supplied code base.

We start by presenting on overview of the software from the perspective of an operator using a spacecraft or system which is implemented using the onboard software. After that, we delve a little deeper, describing the concepts and principles behind the software from the point of a view of a developer using the software to implement custom onboard software for a spacecraft or system.

2.1. A User’s View of the Software

Conceptually, the software as seen by an operator consists of a loosely coupled set of components. A component is a re-usable stand-alone software module which encapsulates a related set of functions and data, and which has a well-defined interface.

Some of the components represent particular hardware subsystems, for example the EPS component provides a software interface to the Electrical Power System (EPS) hardware subsystem which is used to provide regulated electrical power to other hardware. Other components are entirely software based and provide capabilities such as telemetry aggregation or monitoring.

2.1.1. Interacting with Components

The interface to a component takes the form of actions and parameters. Unusual conditions arising when attempting to use an action or parameter give rise to exceptions; to indicate unusual conditions which occur asynchronously to these operations, components may also issue events.

2.1.1.1. Actions

An action is a function that the component can be commanded to perform. This is known as invoking the action. Some actions may accept a single parameter. For example the EPS has a cycleBus action which is used to power cycle one or more power buses. We would refer to this action using the notation

EPS.cycleBus()

While, in this document, we always refer to actions by a logical label, on board each action is actually identified by a numeric ID. The numeric ID for a particular action will depend on the exact build of the onboard software so it may be different across different uses of the FSDK. However, once a software image has been built, the numeric ID will not change.

2.1.1.2. Parameters

Parameters represent data associated with a component. A 'Get' operation is used to read the current value of a parameter, while a 'Set' operation is used to change it. Some parameters are read-only; these often represent some on-board measurement. For example, the parameter EPS.current3v3 represents the current through the 3.3V power bus as measured by the EPS subsystem. Other parameters are read-write and are used to modify the configuration of a component. For example by setting the value of the EPS.watchdogEnable parameter, the user can enable or disable periodic servicing of the EPS watchdog.

The parameters above are scalar, but it is also possible to have vector parameters which have a number of rows of equal length. For example, the subsys.CSLADM component has a parameter subsys.CSLADM.antennaStatus, with 4 rows, representing the status of each of the 4 antennae it controls.

While some parameters have a fixed number of rows, others have a variable number of rows. For example, the list of parameters to be aggregated by an aggregator component is a variable-length parameter. It’s possible to query a parameter to find out the current size of either it’s rows or byte count, depending on the parameter type.

As with actions, each parameter has a unique numeric ID which is used to identify it to the onboard software. Also like actions, whilst the ID is fixed for a given software build, it may change from build to build, depending on how the software is modified.

2.1.1.3. Exceptions

An exception indicates that an error was returned by some on-board function. Each exception has a unique numeric ID. From a user-perspective, they are most commonly encountered inside a 'NACK' (negative acknowledgement) response to a telecommand. Exception codes may also be found inside the 'information' field of certain error-related events.

2.1.1.4. Events

Components are able to generate events to indicate the occurrence of something significant on-board. The occurrence of all events is usually logged, in which case they provide a useful record of what has been happening on-board. Events may also be forwarded to the ground station in real-time. Finally, some events can be used to trigger particular on-board behaviours, such as a mode transition. Events consist of:

-

an event code;

-

a severity code;

-

a source identifier; and

-

event-specific information.

Each event has an event source associated with it so that it’s clear where the event was raised from. Similarly, event sinks can be used to listen for a specific event or all events. Both of these are managed by the containers of the components that use them.

2.1.1.5. Configuration

As mentioned previously, by setting the values of some parameters on a component, the behaviour of the component may be modified. Some of these values form the configuration of the component. The software manages the storage of configuration on behalf of components and typically stores it in non-volatile memory such as FLASH. This permits the configuration of the onboard software to be recovered following a software reset or a mode change. Exactly which parameters on a component are stored in the configuration depends on the implementation of the component itself.

2.1.2. The Spacecraft Database

During the development of the software, a high-level description of the interface to each software component is held in a simple model. When an software image is built this information is used by the tooling to generate a spacecraft database (SCDB) describing all of the actions, parameters, exceptions and events for the spacecraft, including their numeric IDs. The spacecraft database can be exported in a number of forms including a spreadsheet and HTML documentation.

2.1.3. Onboard Data Storage

To permit the storage of data, such as telemetry, received telecommands or onboard events, the onboard mass memory of the spacecraft is organised in to a number of storage channels. Each channel has a unique channel number and a fixed capacity which is configured when the software is built.

Each channel stores data in rows of uniform length. The length of each row in a channel can be set at any time by formatting the channel. For example, when a data channel is assigned to hold the event log, it will be formatted to store rows of data that are 12 bytes in length (this is the size of a single event plus a time stamp).

Each data channel can be configured to be circular or linear. When a linear channel is full, further attempts to add data to it will fail; when a circular channel is full, the oldest row will be deleted to make way for each new row added. The decision to make a channel linear or circular can be made when the channel is formatted.

2.1.4. Onboard Data Handling

Perhaps the most important function of onboard software is the gathering, logging, reporting and monitoring of telemetry. The GenerationOne FSDK provides a number of components, each carrying out one part of the data handling system. These components can be added to a software image and connected together in different ways to suit different missions.

2.1.4.1. Data Pool

Reading the values of some parameters, particularly those representing subsystem telemetry, requires use of one of the spacecraft data buses. Where a parameter is used frequently on board, this could result in the bus becoming overloaded. The purpose of the data pool is to avoid this situation by providing cached versions of on-board parameters, which are refreshed at regular intervals by Sampler components. In most cases, it is preferable to use the data pool version of a subsystem telemetry parameter rather than reading directly from the subsystem component. Note that this relies on a sampler having been configured to refresh the data pool version of that parameter!

The data pool version of a parameter in the SCDB is usually identified by the prefix 'DataPool', so for example DataPool.EPS.current3v3 is the data pool version of the parameter EPS.current3v3. Getting the value of the latter parameter would cause an extra read to be carried out over the platform I2C bus.

If a parameter is considered invalid (because it hasn’t been updated, for example by a sampler) then getting a pooled parameter will cause a read-through. This will therefore return the current value of that parameter. If the read-through is successful, the pooled parameter is updated with that value.

If a Time Action Service (TAS) connection is provided to the DataPool, it is possible to set a lifetime for parameters. When a parameter has been updated with a valid value, if it is not updated with a new value within the lifetime period, it will be considered invalid. Any attempts to get a pooled parameter which has exceeded it’s lifetime will therefore cause a read-through.

2.1.4.2. Samplers

Samplers are responsible for refreshing the values of parameters in the data pool. Each sampler may be configured with a list of parameters to update and an independent update frequency.

2.1.4.3. Aggregators

Aggregators are used to aggregate the values of several parameters and make the aggregated value available in a compact bit-packed form suitable for transmission to ground or for logging into a channel. The list of parameters aggregated is configurable and can be modified at any time. For a list of parameters that will not be modified, there is the component FixedAggregator.

2.1.4.4. Monitors

Monitors are used to periodically check the value of one or more parameters and raise an event if they go outside of a configured range. Each check specifies a parameter, a valid range and an event to raise if the parameter value is out of range. Checks can be modified and enabled or disabled at any time.

2.1.4.5. Data Loggers

Data loggers are used to log periodically the value of a parameter to a data channel. The logger will get the value of a parameter periodically, and add the value to an internal buffer. After a number of these get operations, the entire internal buffer will be written to a storage channel. This double-buffering helps to make more efficient use of the underlying storage system.

It is common to use an aggregator as the input to a data logger. This permits you to log the values of multiple parameters at once.

2.1.5. Automation

A number of components are provided to allow autonomous operation of many aspects of the software and spacecraft hardware.

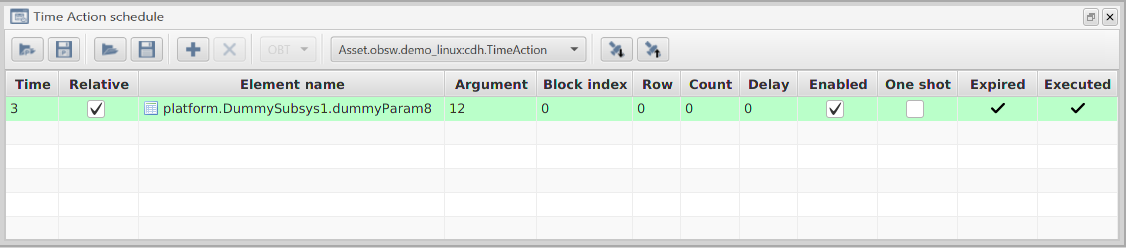

2.1.5.1. Absolute Time Schedules

An absolute-time schedule allows spacecraft actions to be triggered at a particular Spacecraft Elapsed Time (SCET). This is usually the number of seconds since the initial on-orbit activation of the spacecraft. Each schedule entry consists of an activation time and an action to be invoked at that time.

Multiple time schedule components can be used to permit different schedules to be defined and enabled and disabled independently.

2.1.5.2. Orbit-Relative Schedules

An orbit-relative schedule allows spacecraft actions to be triggered at a particular time relative to the start of a particular orbit. This relies on an additional component to do orbit detection and announce the start of orbits using an event.

An orbit-relative schedule can be quite sophisticated as each entry can repeat at predefined intervals over a specified range of orbits.

2.1.5.3. Event-Triggered Actions

An onboard software build may also support one or more event-action lists. These simply associate component actions with onboard events. When the listed event is received, the associated action is invoked.

These EventAction components can be combined with monitors to create simple fault detection, isolation and recovery (FDIR) mechanisms which detect out of range parameters and respond by automatically invoking a recovery action, such as changing mode.

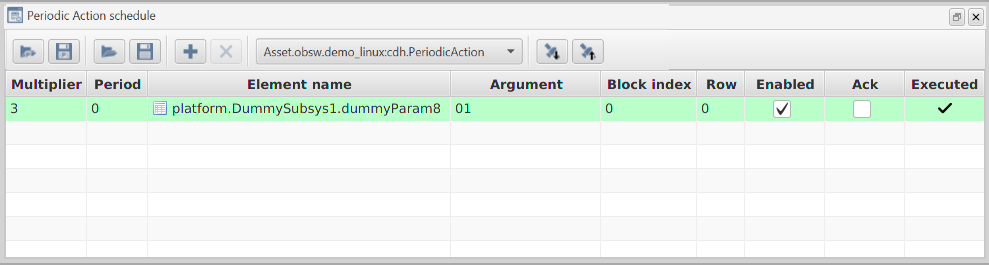

2.1.5.4. Periodically-Triggered Actions

Actions can be triggered periodically using a PeriodicAction component. These are set up to invoke actions at individual periods. These can be used to act as a system watchdog to reset declared components.

2.1.5.5. Scripting

The GenerationOne FSDK supports sophisticated scripts written in a custom byte code and executed by Script components. Each Script component is an independent virtual machine into which scripts can be loaded from onboard storage channels. Scripts provide new actions and parameters to the onboard software, just like any other component.

Scripts are typically used to simplify and customise payload operations, but can be used for a wide range of onboard automation tasks.

2.2. A Developer’s View of the Software

The previous section described what the GenerationOne FSDK 'looks like' from the perspective of a user, or operator. It’s now time to dig a little deeper and to investigate how onboard software is constructed.

2.2.1. System Architecture

The main functions of a system built from our onboard software, including most of those described in the previous section, are provided by application components. These components rely on three further elements:

-

system components, such as drivers and communications protocol handlers;

-

services, which provide an abstract interface to many system components;

-

libraries, which form part of the infrastructure, providing key system functions.

These three elements form what we refer to as the framework.

Finally, the system components and libraries of the framework rely on a Platform Support Package (PSP). This is either supplied by us, as part of the FSDK, or by the vendor of the target platform, and contains the basic software routines necessary to access the hardware. In some cases we may provide modifications or patches to vendor-supplied libraries to help integrate the library with our onboard software architecture.

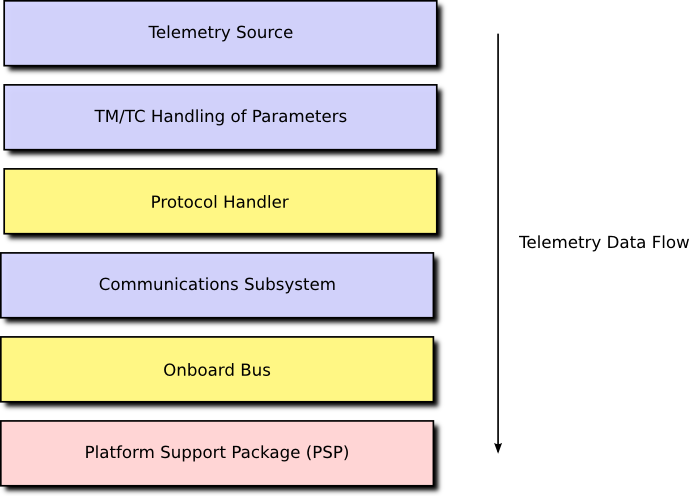

A high-level depiction of the architecture, showing the relationship between the various elements, is presented in Figure 1.

This architecture is perhaps best illustrated with some examples. Typical application layer components would include:

-

subsystem components, which each provide a high-level functional interface to a single spacecraft subsystem such as the EPS;

-

the data pool of key parameter values;

-

data handling components, such as samplers, monitors, and data loggers;

-

telemetry/telecommand (TM/TC) components which provide an interface between the various application components and the communications systems to ground.

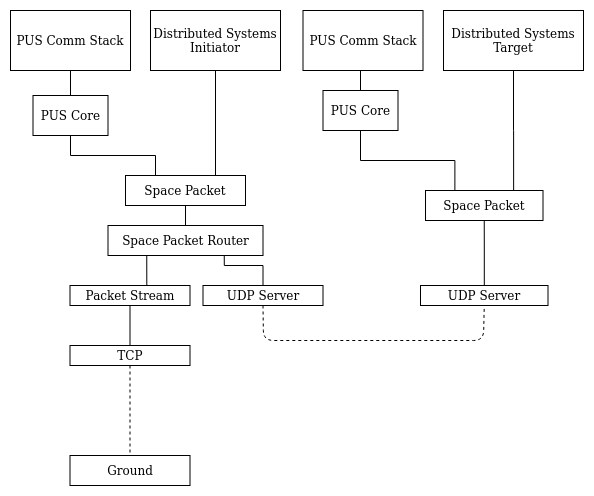

In order to send telemetry, a TM/TC component would place the necessary data in a buffer and request that it be transferred using, for example, the Packet Service (PS). The service handler for PS will map this request onto, again for example, a system component acting as a protocol handler. This protocol handler will typically package the data into a valid packet and then send this new packet to the communications subsystem component, again using PS. The communications subsystem component will then transfer the data to the actual hardware using PS or the Memory Access Service (MAS). The service handler will map this request onto a system component providing access to the hardware interface to the device, such an onboard communications bus. The actual interface to the bus is typically provided by functions in the PSP. This sequence of interactions forms a communications stack where the interaction between each element of the stack is via a communications service such as PS or MAS. This is shown in Figure 2.

The communications services, PS and MAS, provide a regular interface to the functional services of other components without requiring knowledge of those components. The use of services in this way means that any component in the stack can be replaced without affecting any other component. This allows you to move your software between platforms easily.

2.2.2. Components and Containers

A component is simply a collection of functions which are centred around two things:

-

parameters, which are the various elements of data associated with the component; and

-

actions, which are the various operations that may be performed on the component.

Our components follow the principles of Object-Oriented Programming (OOP), so parameters are mostly the same as fields or attributes, and actions are mostly the same as methods or routines. Each action is implemented in a single C function. Each parameter is implemented through a number of C functions, called accessors, which provide access to the underlying data. The parameters and actions of a component may be accessed directly, by calling these functions, but they may also be access generically by using an identifier. These identifiers provide a mechanism through which component functionality can be accessed from ground via telecommand.

Every parameter and action in the system is assigned a unique ID, these IDs are mapped onto the action and parameter accessor functions of a component by a simple set of wrapper functions known as the component action source and parameter source respectively. The action and parameter sources translate between ID-based requests and the specific functions of a component. As such, these functions wrap-up access to the component and form part of a component’s container.

A container may also permit access to a component’s functions via a service provider interface, such as a Packet Service provider. This allows the component to be registered with, for example, PS. A request to send a packet using PS, on a specific channel, will then be routed by the PS service handler to a standard interface provided by a component container. This will then invoke an underlying action on the component itself.

As well as providing regular access to a component’s actions and parameters, a container helps manage the life-cycle of a component: component start-up, or initialisation, and component shut-down, or finalisation. A component may also wish to store part of its internal configuration data persistently, to permit the system to return to a previous configuration after a restart. The component’s container will provide functions to ease the handling of his configuration data.

Application and system components are identical, except for the fact that system components do not provide access to actions and parameters via sources.

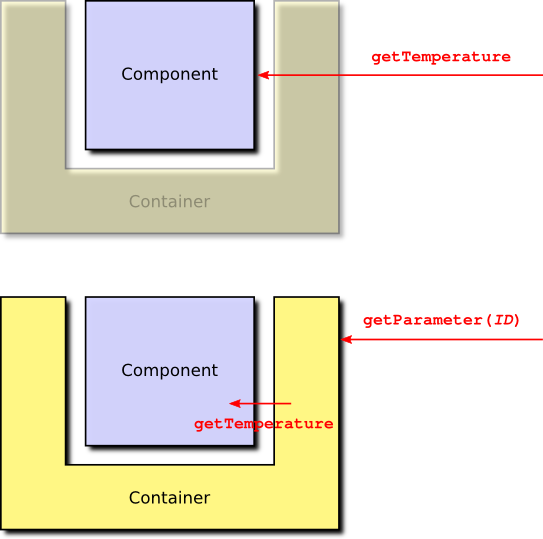

For example, consider a subsystem component which provides a temperature parameter. As this parameter is read-only (in the absence of, for example, heaters, it makes no sense to be able to modify a subsystem temperature) the component needs to provide a single accessor function called getTemperature. If temperature is accessed directly, getTemperature can be used. If temperature is accessed by ID, the container functions of the parameter source are used to translate the ID-based access into a call to getTemperature. This is shown in Figure 3.

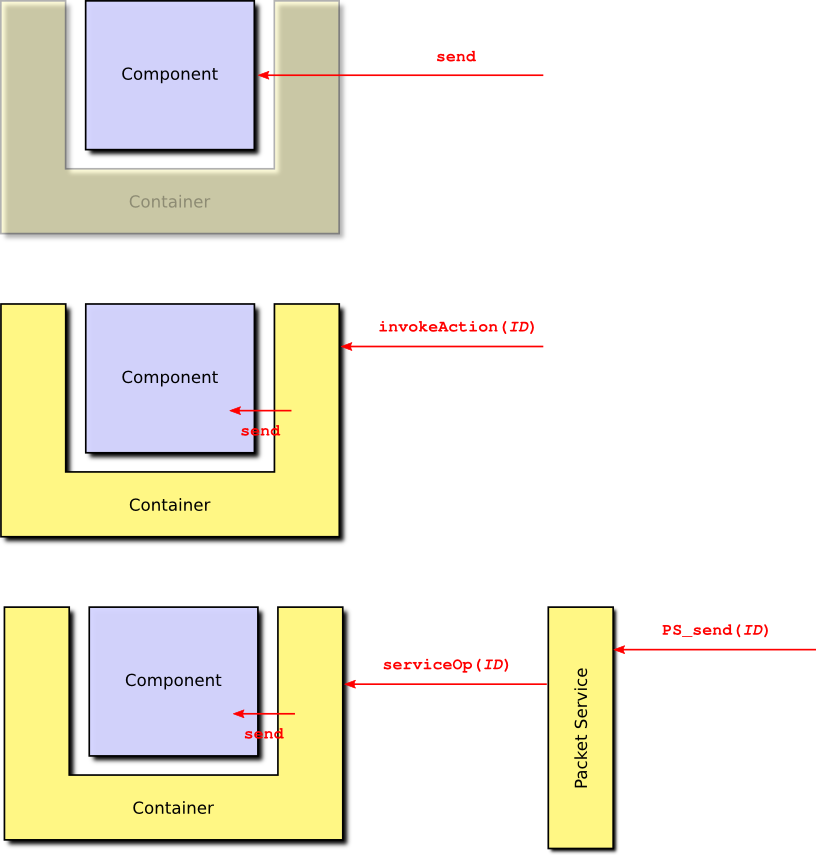

Similarly, an action function, such as send, may be accessed directly, or it may be accessed using an ID, via the action source in the container. The component may also permit access to send using the packet service, in which case another component would invoke a packet service function which accesses the component container which then invokes the component send function. These three cases are shown in Figure 4.

A component which simply responds to requests from other components is known as a passive component. A component may also provide one or more task functions. These are functions which may be attached to, or called called from, a dedicated task. This gives the component its own thread of execution, in which case the component is known as an active component.

2.2.3. Deployments

When writing the code for a component you are actually creating a component type. This is much like a class in OOP. It provides the template for one or more component instances, in a similar way that a class is the template for one or more objects. To create some executing software it is necessary to instantiate a number of components and connect them together. This is called a deployment.

A deployment specifies:

-

what components there will be in the system and how they will each be configured;

-

how the parameters and actions provided by each container may be accessed globally;

-

how the service operations provided by each container may be accessed globally; and

-

the tasks that are related to the component in this deployment and which component task functions they are attached to.

Deployments are specific to a given platform and contain the initialisation code necessary to get the underlying platform up and running. Once the platform is running, the deployment initialises the component manager which is responsible for managing the life cycle of all components (initialisation, configuration and finalisation) and their attached tasks. The deployment then initialises the various services. The component manager then continues by initialising all components. The initialisation process is broken down into three phases:

-

container initialisation;

-

internal component initialisation; and

-

inter-component initialisation, initialising the connections between components or between components and services.

Once the components are initialised, the component manager initialises component tasks. Finally, the deployment permits the task library to begin executing tasks and the component-based system springs into life!

2.2.4. Development Process

The development of any onboard software using the GenerationOne FSDK is likely to follow the same general pattern. Rapid onboard software development, particularly for nano and small satellites, is likely to be collaborative and iterative. We have therefore tried to design the GenerationOne FSDK to support the iterative refinement of onboard software as much as possible.

-

The first step is to identify the major hardware elements of your spacecraft and how those will be represented in software. It is likely that the FSDK will already have some support for your hardware subsystems, but more exotic hardware, especially payloads, may require custom components.

-

Next it is important to identify your concept of operations. How do you want to operate your spacecraft? What does it need to do autonomously? How much data does it need to store and under what conditions? Answering these questions will help you decide what application layer components are necessary and how they should be connected.

-

You’re now ready for a first cut of your onboard software. Using an example deployment as a starting point you can now deploy components to match your spacecraft subsystems and operational concept.

-

Time to try it. Build your deployment and either deploy it onto your hardware, or if you have chosen to target Linux, it will be ready to execute on your workstation. The TMTC Lab graphical user interface can now be used to interact with your onboard software and test its functionality.

-

Identify places where the existing components do not fulfil your mission needs. That might be in areas like mode management, which is typically mission specific, or interfacing to your payload.

-

Design one or more components to meet your needs and describe the interface to each component type in an XML file. You can use the XML files for existing component types as a guide. Once you have a complete interface, use the container generator to generate container code and initial stubs for all component functions.

-

You can now start to populate your new component types with code. You may find it useful to use the unit test framework included with the FSDK to test your components before deploying them.

-

Add your new components to your deployment, rebuild, execute and test!

This process can be repeated as often, and rapidly, as desired for your mission development process.

2.2.5. Basic anatomy of a Component

This section gives an overview of what the different elements are that make up a component. Some of these elements appear in all components, others will appear depending on the design of a specific component.

2.2.5.1. Life-cycle

The most important element deals with the life-cycle of the component, handling the initialisation and the finalisation stages. These are split up between internal initialisation and inter-component initialisation and then inter-component finalisation and internal finalisation. The internal stage is used to set up a valid initial state where all the components can be initialised properly before they are connected. After this, the inter-component connections can be made, which can include the initialisation stage having access to other components. All components have local initialisation and finalisation; inter-component initialisation and finalisation are optional, and can be included if the component has links to other components, or services, which need initialising and finalising.

2.2.5.2. Configuration

The configuration is a system-wide store into which each component can choose to add information about its own, internal, state or configuration. The configuration is usually persistent (e.g. in FLASH), and is typically used to make sure that the configuration of an OBSW system is maintained even if the computer reboots. Every component can choose how much, and what, information to store in its configuration. At initialisation time, each component is asked how much configuration space it needs, the configuration manager then reserves that amount of space in the system configuration. Once the system is running, a component cannot request more configuration space, it must always keep within the value it provided during initialisation. If configuration is used by the component, it will provide functions to allow the configuration manager to request the current configuration of the component, and to set the current configuration. In a special case, if a request is made to set the component’s configuration from a data buffer with a size of zero, the component is expected to re-initialise its configuration to default settings.

Components do not have to use a configuration; if they choose not to, then the configuration elements of the component interface are not present.

2.2.5.3. Tasks

As well as a configuration, a component may also contain tasks. The tasks associated with a component are not created in the component code, instead they are created in a deployment. This puts full control of what tasks there are in the system, and how they are configured, in the hands of the person assembling components, rather than the person writing them. This, in turn, makes components much more reusable.

The component is responsible for supplying the code which will be executed for each task. There are three types of task: periodic tasks, sporadic tasks and interrupt tasks. Periodic task functions are called periodically at intervals defined by their period. Sporadic tasks are called intermittently when they have something to do. Sporadic tasks have an associated data queue and task execution is triggered when something is placed on the queue. Interrupt tasks are used by driver components to respond to low-level hardware interrupts.

The code in a task function is expected to execute, and then return. The next time the period expires (for a periodic task), or there is data on the task queue (for a sporadic task), or the interrupt is asserted (for an interrupt task) the function will be called again. A periodic task function does not contain a loop which waits for the period to expire, that is handled by the task itself. Similarly, a sporadic task function does not block waiting for more data, the task itself handles that.

2.2.5.4. Actions and Parameters

The most elements of a component are the action handlers and parameter accessors that it provides.

Action handlers are very simple: they are functions which are called when an action is invoked either on board or from ground. The simplest actions take no arguments. Alternatively, an action can take a single argument which is always a string of bytes. This argument will always be transferred from the invoker (e.g. ground) with no correction for byte order as is done for parameter values. The argument can either be of fixed length, or it can be of variable length. This means there are three types of action function: those that take no arguments; those that take a single, fixed-length argument; and those that take a single, variable-length argument.

Parameter accessors are called when the value of a parameter is being requested (a 'Get') or being specified (a 'Set') by either another part of the onboard software, or by ground. A read-only parameter will have a get accessor function, in addition to this a read-write parameter will have a set accessor function. As we described in Section Section 2.1.1.2, a parameter can vary in size in one dimension. This variation can either be in the number of rows a vector parameter has, where each row is a fixed size; or in the size of the row, if the parameter is scalar. The type of a parameter determines if the data contained in the parameter can be interpreted as a number, or if it is 'raw' data. This distinction is important, as the framework will automatically convert the byte order (the endianness) of parameters which are numbers when they are transmitted or received to/from ground. The framework will not modify the byte order of raw parameter values. Parameters can have the following types:

-

unsigned integer, with any bit length up to 32-bits supported (referred to as uint);

-

signed integer, with any bit length up to 32-bits supported (referred to as sint);

-

bitfields, with any bit length up to 32-bits supported (referred to as bit);

-

raw values of a fixed size (referred to as raw);

-

raw values of a variable size (referred to as varaw).

All fixed-length types (everything except for variable-length raw values) can be used as either scalar or vector parameters. Variable-length raw values can only be scalar parameters. The first three types, unsigned and signed integers and bitfields, are all treated as number, or value, types. These are the ones that the framework does automatic byte-order conversions on.

3. FSDK Installation

This chapter describes system requirements and installation steps needed to use the FSDK natively on your machine.

Note that we also supply a virtual machine on which the FSDK is pre-installed. This may be run on a variety of host systems using VirtualBox, and is often useful for the first steps in using the FSDK.

If you plan on using the virtual machine you can skip straight to Section 4.

3.1. System Requirements

We have developed and tested the FSDK on Linux, specifically Ubuntu 18.04 LTS. It is likely that other Linux distributions can be used, but this has not been extensively tested and we are not be able to support other distributions in general. Using the GenerationOne FSDK on Windows requires the installation of a Unix-style environment such as Cygwin.

3.1.1. Build Tools

The following tools are required for building GenerationOne onboard software:

-

GNU make;

-

a gcc toolchain targeting your platform, we provide toolchains for some target platforms (e.g. ACS Kryten);

-

the following commands/utilities: echo, find, grep, mkdir, rm, sed, tail, tee, touch;

-

ruby 1.8 or greater to support unit testing;

-

doxygen for building API documentation.

3.1.2. Development Tools

A core part of the FSDK is the code generation tool, codegen, which is used in many different tasks in the FSDK workflow.

codegen is run from the command line, and Java 11 is required to run it.

3.1.3. Ground Tools

Java 11 is required to run TMTC Lab. Specifically Java SE 11.0.13 or later is recommended. There are no other requirements for TMTC Lab.

The Python API requires Python version >=3.7. See the HTML Python documentation (GNDSW/python/doc/html/index.html) for installation and usage details.

3.2. Installation

Installation is primarily a matter of copying all files from the installation media to a suitable location on your workstation. After that:

-

toolchains, if required, should be expanded and placed somewhere suitable (e.g. /opt), ensuring that the binary sub-directory is on the path;

-

Unity and CMock, used by our unit testing framework, should be installed. See Section 3.2.1; and

-

the

codegentooling should be installed. See Section 3.3.

All build scripts use relative path names so the absolute location on your workstation shouldn’t affect your ability to build the software.

3.2.1. Unity and CMock

Our unit testing framework is based the tools Unity and CMock from throwtheswitch.org. We distribute patched versions of these tools under the OBSW/Tools directory.

To extract and install the tools, run the following commands from this location:

-

Specify a writable location for ruby gems to be installed:

$ export GEM_HOME=$HOME/.gem-

Extract the tools, apply patches, and install the ruby gems:

$ ./extract.sh-

Copy the Unity and CMock source files to the unity library in the Source directory:

$ ./copy2lib.sh3.3. Command-line Tooling Installation

In order to execute the command line tooling (CLI), the Tooling/bin directory should be added to your path. The tooling also comes with a manpage, which can be installed by copying the contents of Tooling/manuals to /usr/local/share/man/man1/, this will require super user permissions.

Once the manuals have been copied into place it is necessary to update the mandb with sudo mandb, again requiring super user permissions.

For convenience we have provided an install script Tooling/install_tooling.sh, which will add the Tooling/bin directory to your path and install the manual pages, prompting for a sudo password when copying the manuals.

Help information can be obtained by executing codegen with the -h or --help argument, or if the manpage has been installed, by running man codegen.

It is assumed that the CLI tooling will be run on a Linux system. For information on how to use the CLI tooling refer to Section 5.

3.4. Directory Structure

The root product directory includes five sub-directories. These are:

-

Documentationcontains documentation for the GenerationOne FSDK describing how to install and use the software. -

GNDSWcontains tools, such as TMTC Lab, to act as a basic ground segment for interacting with onboard software. -

Licencescontains the licence for the GenerationOne FSDK as well as licences for 3rd party libraries used by the FSDK. -

OBSWcontains the onboard software source code comprising platform support packages, the framework, libraries of components and example deployments. Build tools and toolchains for supported platforms are also included here. -

Toolingcontains thecodegentool used during software development with the FSDK.

Most sub-directories contain readme.txt files to give a brief description of their contents and purpose.

The root directory also contains a file named version.txt which uniquely identifies your FSDK software version. The version information is encapsulated in a single version string at the end of the file. If you need to contact us for support, supplying this version string to us will help us track the exact version of all files that you have.

3.4.1. Using external source directories

GenerationOne now supports source code that is not part of the FSDK directory structure by making use of environment variables referenced in a project’s config file.

This is described in Section 7.1.1.

4. Getting Started

This chapter describes how to build and run a sample Linux deployment included with the GenerationOne FSDK. The intention is to give you a practical example of the concepts that have been discussed in Section 2.

If you have installed the FSDK on your own machine, as described in Section 3, you can skip to Section 4.2.

If you have not installed the FSDK on your machine and plan on using the VM instead, you must first carry out the steps given in Section 4.1.

4.1. The Virtual Machine

The virtual machine has been set up to help create a simple entry point for users of the GenerationOne FSDK. It requires the use of VirtualBox, which can be found at https://www.virtualbox.org/wiki/Downloads.

We recommend working with the GenerationOne FSDK through the virtual machine if you aren’t using Ubuntu 18.04 LTS. The supplied virtual machine has been tested on VirtualBox version 6.1.

We also recommend running the virtual machine on a 64-bit host machine as the guest OS is 64-bit. If you are running a 32-bit host, then you may need to make sure that hardware virtualisation is enabled in the system’s BIOS. More information can be found in the VirtualBox FAQs and documentation.

4.1.1. Importing the Virtual Machine

Open up the Oracle VM VirtualBox Manager and click 'File' → 'Import Appliance…'. Find and open the .ova file that came with your release. Now click 'Import' and the GenerationOne FSDK VM should appear on your list of virtual machines. Note that you can import the .ova file directly into VirtualBox. The machine is set up as dual-core, for better compatibility, we advise that you adjust the VM’s settings to maximise the resources that it will use.

4.1.2. Getting Started with the Virtual Machine

With the 'GenerationOne' appliance selected, click 'Start' to start the VM. Note that another copy of this manual can be found on the VM’s desktop. Holding the host key (default is right-ctrl) and pressing 'F' will bring the virtual machine full screen, which we find to be easier to work with, especially where the virtual machine is used on a single desktop of multi-desktop host environment. Other functions for use with VirtualBox can be found in it’s documentation.

The login details for the VM are:

User name: gen1-user

Password: BrightAscension

When you start the VM, you should be presented with a basic desktop which contains:

-

Short-cut to the user manual

-

A launcher icon for starting TMTC Lab

-

A launcher icon for opening the command-line terminal

-

A launcher icon for opening the file system.

The FSDK is used from the command-line terminal, and is available in the `gen1-user’s home directory.

4.1.2.1. Setting Up USB Controllers for Linux Hosts

We have set up the virtual machine to connect to USB devices on the host machine for interfacing directly with onboard computers (you can check the list of configured USB filters in VirtualBox Manager under 'Settings' → 'USB'). To be able to use these devices, the user on the host OS must be in the vboxusers group. Further information on this topic is available in the VirtualBox FAQs and documentation.

4.2. First Steps with the FSDK

You should now have a working FSDK environment - either natively on your own

machine, or through the supplied VM. In this section we guide you through

generating, building and running the demo_linux deplyoment.

This section assumes that you have a basic working knowledge of using the command line.

4.2.1. Building Libraries

When building a project for the first time, you need to call make from that project’s directory. For example, to build the app project:

$ cd gen1/OBSW/Source/app

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ makeIf this is the first time building, make will build all the

dependencies. If the dependencies have already been built, it will only build

the app project itself.

If changes have been made to a dependency, the following command will force the build system to check for changes to `app’s dependencies to check whether it needs to rebuild them:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make forceDepending on the speed of your workstation these builds can take several minutes.

For further information on the build system it’s possible to bring up help:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make helpThis will list the valid build configurations for the library. These specify which OS and board the build will target, and can be used on the command-line like so:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make force CONFIG=kryten_failsafe4.2.2. Running Unit Tests

The build system can build and run unit tests as well. The make

command will build all unit tests for the library, and these can be run after

the command completes.

For example, to run the test for the CSLEPS component, run the following binary:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ bin/linux/testCSLEPSThe test should execute and the last line of the test output should say 'OK'.

The line before that gives a summary of the test results. Binary executable

files for all unit tests are in the bin subdirectory.

Note that tests include checks that components fail correctly, so there may also be error logs, but this is normal. Look for the Unity output in the console, which should look similar to this:

-----------------------

279 Tests 0 Failures 0 Ignored

OKThe build system can also specifically build and run unit tests. To build all tests:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make testsTo build and run all tests:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make testrunTo build a single test, in this case for the CSLEPS component:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make testCSLEPSTo build and run a single test, in this case for the CSLEPS component:

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make testrunCSLEPS4.2.3. Generating Doxygen Documentation

The FSDK source code is commented with extra tags to permit the generation of cross-referenced documentation using Doxygen. You will need to make sure you have Doxygen installed and on your PATH to generate this documentation.

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ make doxThe build system will invoke Doxygen for the application component source tree. HTML documentation will be produced; you can find the output in the doc subdirectory. Doxygen generates a great deal of output; start with the file called index.html.

Equivalent documentation can be generated for any library in the FSDK.

4.2.4. Generating the Spacecraft Database

The spacecraft database is used by the TMTCLab ground software to communicate with the deployment we are going to run.

Generating an SCDB requires the use of the codegen tool on the command-line.

gen1/OBSW/Source/app$ cd ..gen1/OBSW/Source$ codegen deployment generate demo_linuxSection 5 describes the FSDK’s command line tooling in more detail.

4.2.5. Building the Sample Deployment

Having built the supporting libraries, you can now build the sample Linux deployment. This is in the demo_linux directory and can be built just as with the libraries:

gen1/OBSW/Source$ cd demo_linuxgen1/OBSW/Source/demo_linux$ makeNote that this command will not build dependencies. To check all the dependencies of a deployment, and build them if needed, run:

gen1/OBSW/Source/demo_linux$ make force targetIn either case, the build script follows the same pattern as before, but this time an executable is generated: bin/linux/demo_linux. This is the deployment, and is ready to be executed.

4.2.6. Starting the TMTC Lab Software

TMTC Lab is included as part of the FSDK as an executable JAR file. In some environments you may be able to double-click the JAR file to start the software. Otherwise, you may need to start it from the command line:

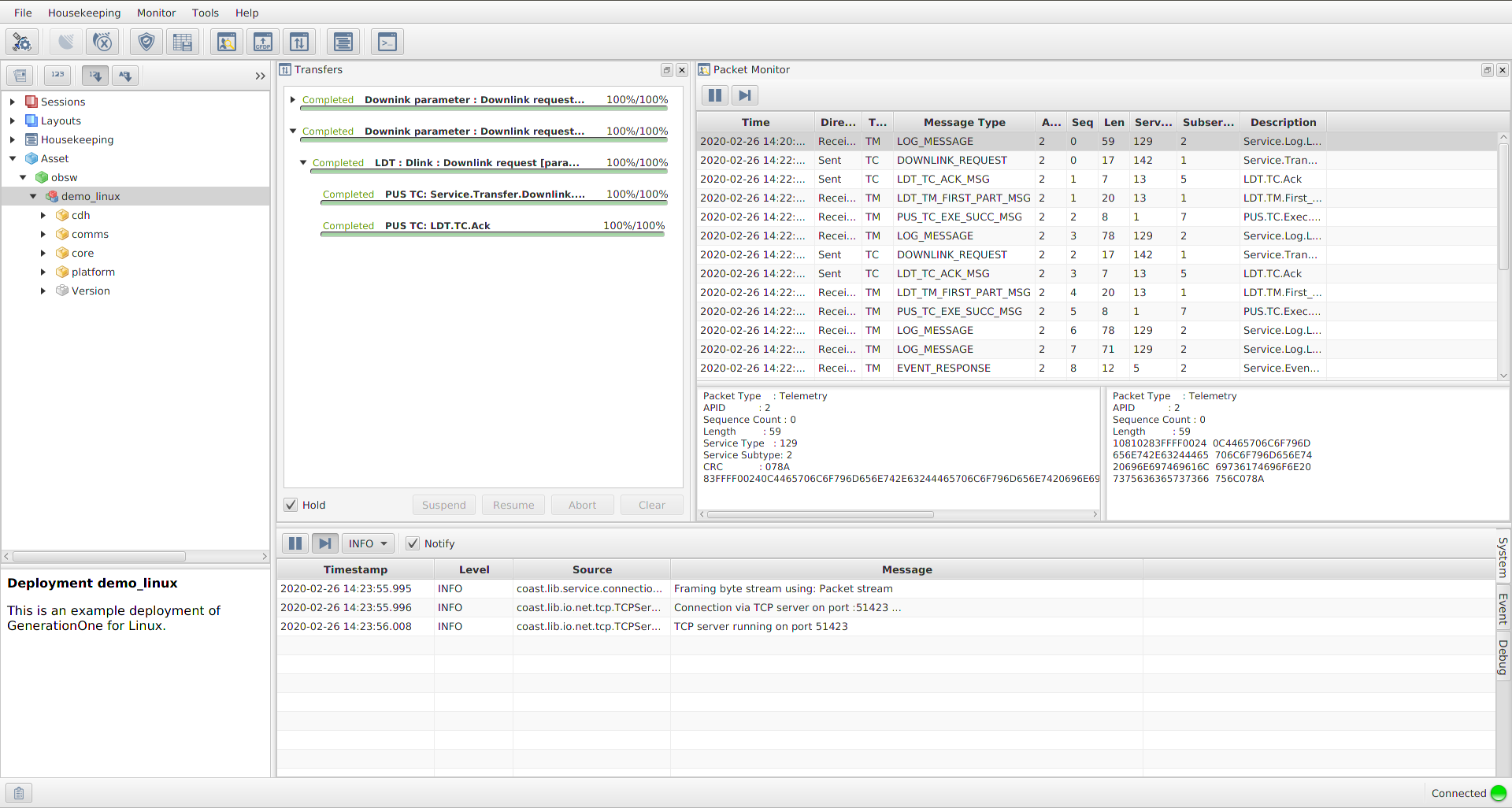

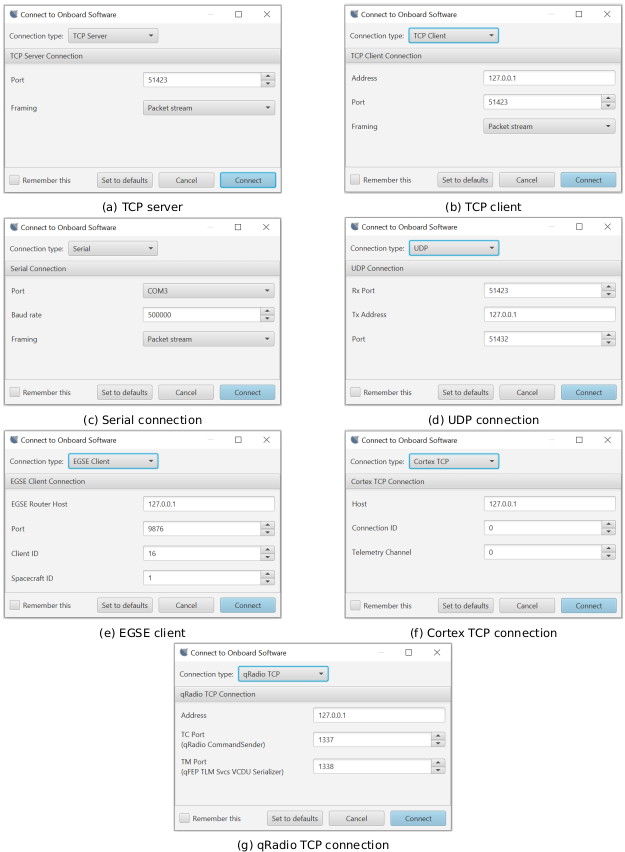

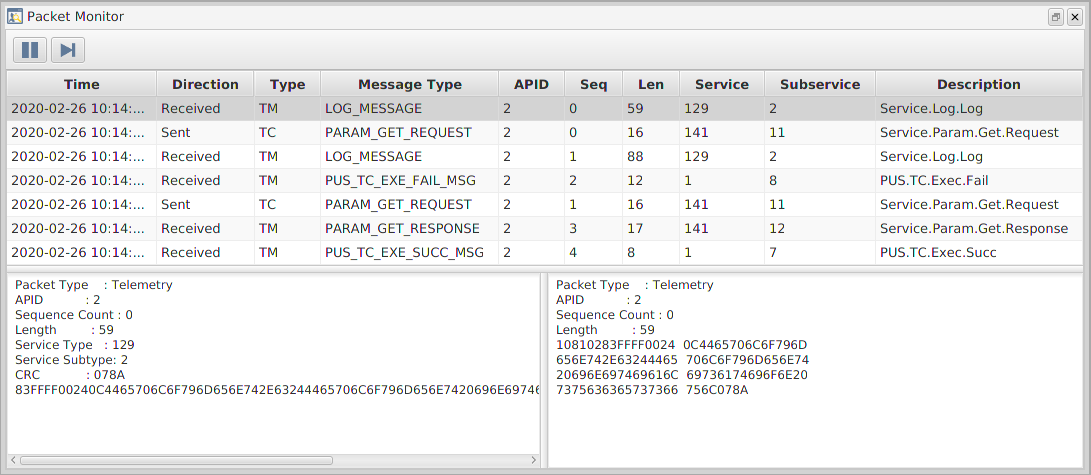

gen1/GNDSW/TMTCLab$ ./runLab.cmdThis should launch the TMTC Lab software and display the main window. The TMTC Lab main window with open Packet Monitor and Transfer is shown in Figure 5. Adding the option -help will provide information on other options that can be used with the software.

When you have finished using TMTC Lab, it’s best if you close it (or at least disconnect) after you stop the deployment from running. If you don’t do it this way round, various resources to do with the connection between the onboard software and TMTC Lab are not properly freed. You would then not be able to start another deployment immediately, rather you would have to wait for a period of time (usually 5-10 minutes) for Linux to detect a time out and free the resources for you.

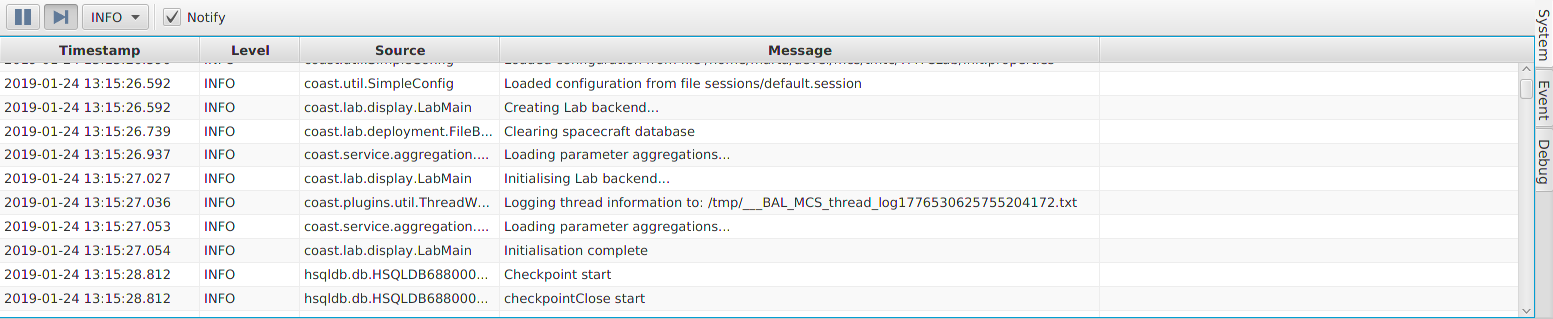

The TMTC Lab main window contains smaller windows with different functionalities. In a example on the Figure 5 clockwise from top left these are:

-

the Mission Explorer;

-

the Transfer window, showing finished or in progress transfers;

-

the Packet Monitor window, showing all traffic over the space link, each line represents a packet;

-

the System/Event/Debug Consoles.

Details about TMTCLab functionalities are presented in Section 9.

4.2.7. Running the Deployment

Before running the demo_linux deployment, make sure that TMTCLab TCP server is running as described in Section 6.3.5.

To run the deployment from the command line simply execute the binary file we built earlier:

gen1/OBSW/Source/demo_linux$ bin/linux/demo_linuxThe deployment will show various messages showing that it is starting up and configuring various aspects of the system. It will not return so runs indefinitely. You can stop the execution of the deployment using CTRL-C on the command line.

demo_linux uses a TCP client and the initialisation data matches the defaults of TMTC Lab and as such, it should connect successfully.

4.2.8. Basic Telecommanding via Spacecraft Database

The TMTC Lab main window can be used to communicate with the deployment. There is an in-depth chapter on TMTC Lab in Section 9. For now, we will cover basic connection and telecommanding.

In order to communicate with the deployment we need to open the SCDB. This is done as follows:

-

Click 'File' → 'Manage deployments…'

-

Select the top row of the table, then click 'Set deployment…'

-

Set the 'Definition file' to be the

deployment.scdbfile you generated earlier. -

Click 'Open'

-

Close the 'Deployment Management' window

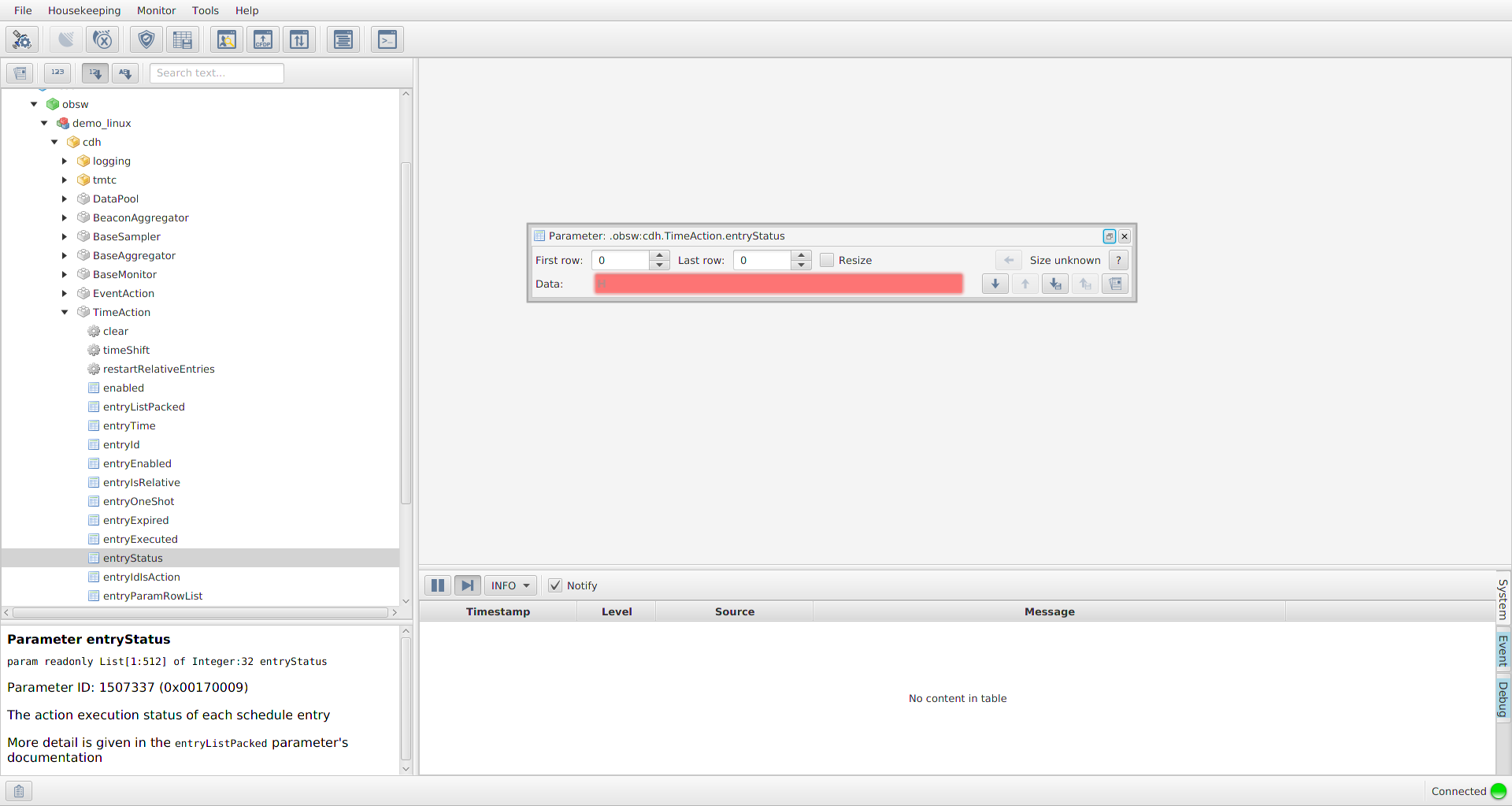

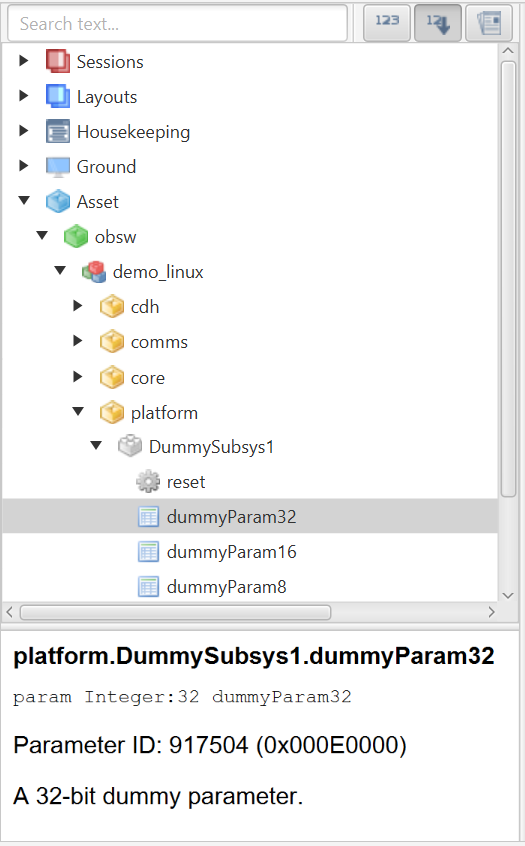

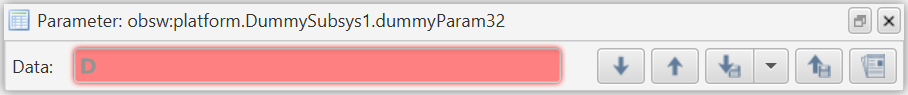

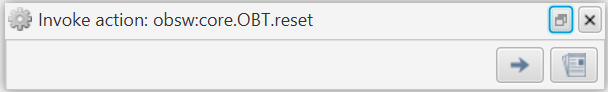

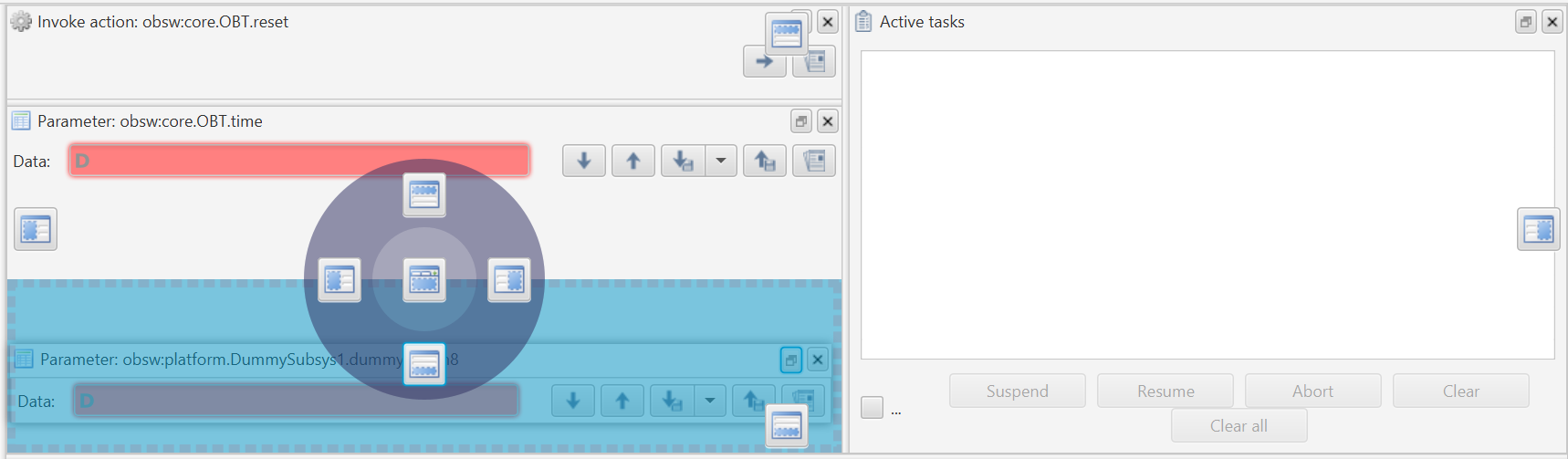

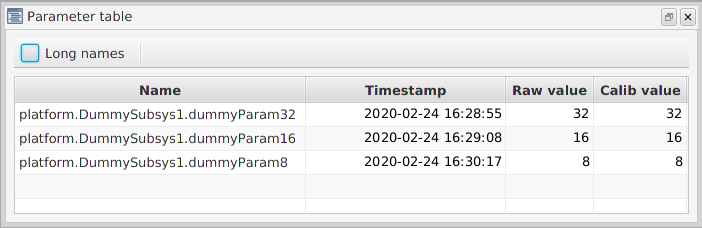

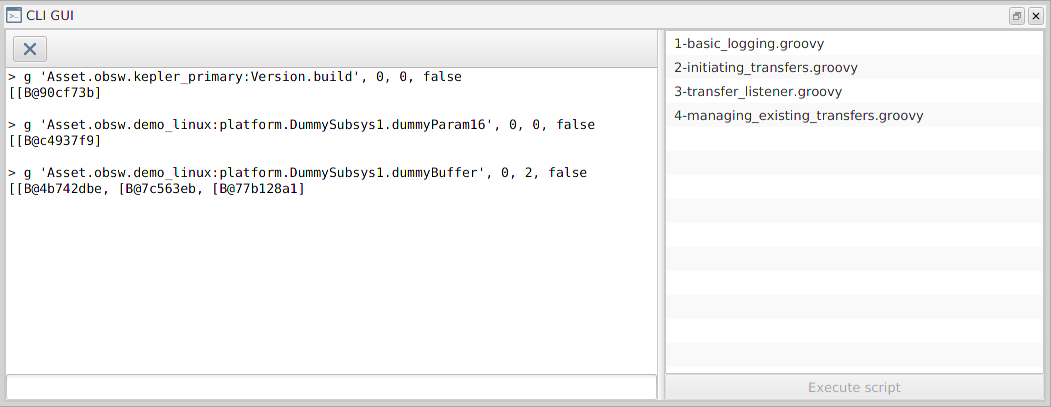

You should be greeted with a window that looks like Figure 6. From here, you can explore the deployment as demonstrated in the image. There are dummy components included in the demo_linux deployment that you can use to get familiar with the interface. If you open the DummySubsys1 tab you will see there’s an action called 'reset' and 3 parameters that hold 8, 16 and 32 bit numbers. If you select the dummyparam8 parameter, you will see it’s signature, ID and a description. There are also Get and Set buttons available. If you click Get, you should see '08' appear in the 'Data' section and also the text 'Parameter accessed successfully' near the bottom. If you change the value to a different number and hit set, you should see the same output text. If you clear the data field and click Get again, it should return the value that you set.

If you now select the 'reset' Action you will see that the interface has changed slightly. Again, you are presented with the signature, ID and a description of the action. You are now able to 'Invoke' an action. Note that there is a disabled argument field; It is here that you would pass in arguments to be used during an invoke. If you click Invoke, the values of the dummySubsys1 component should be reset. You can check this by returning to dummyparam8 and clicking Get, it should return the value '08' again.

TMTC Lab is still running behind the SCDB window, you can minimise it by clicking the icon in the top-right corner. Doing this should reveal that there are now packet logs in the Packet Monitor window. These should mimic the actions that you just under-took while interacting with the deployment. As mentioned in Section 4.2.6, you should only disconnect from the packet service after stopping the deployment when you wish to stop using the TMTC Lab.

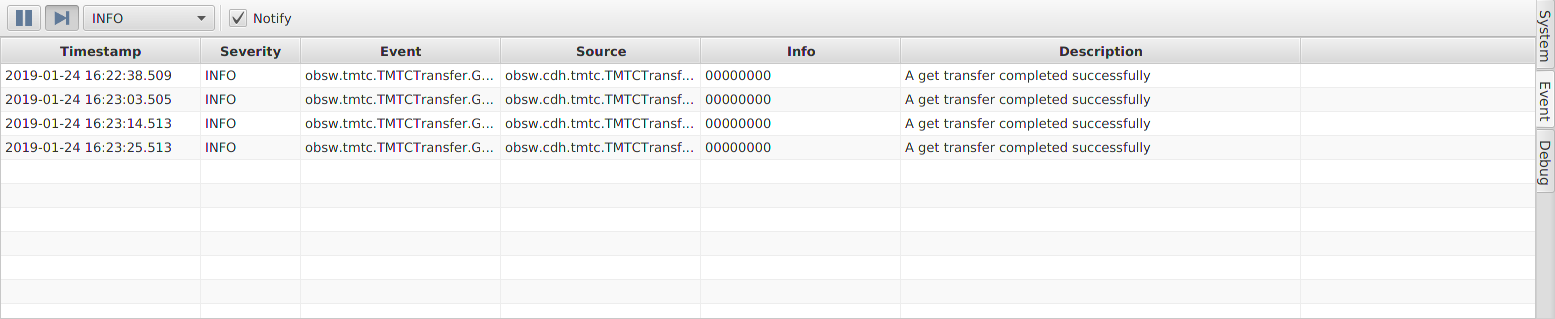

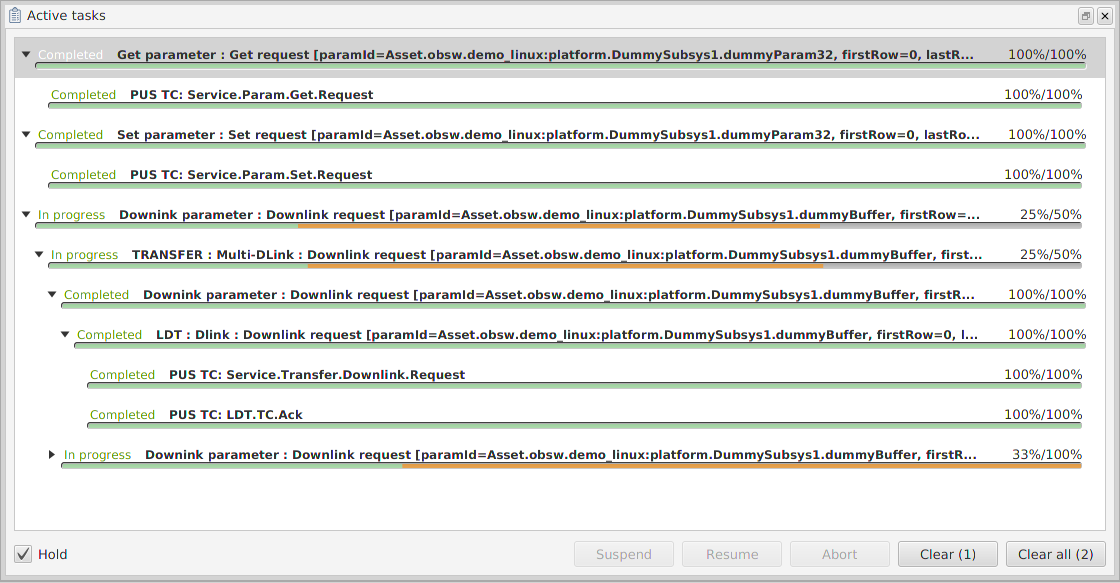

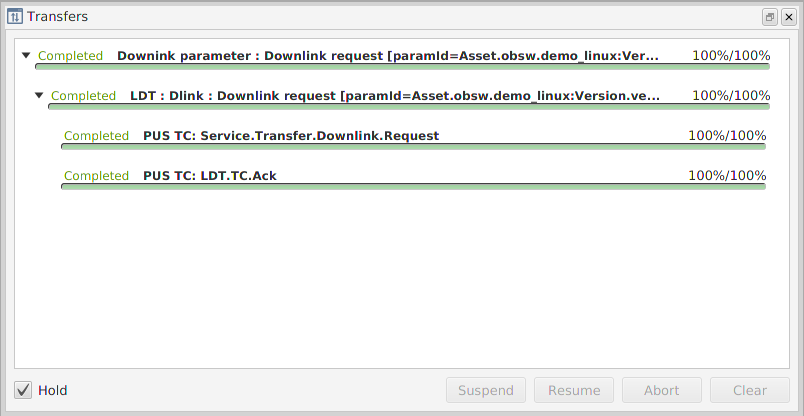

4.2.9. Downlink/Uplink Transfers

For each parameter you can get its value or downlink it. If the parameter is not read only, you can also uplink a value from the file. Progess might be followed in window 'Transfers' opened by clicking one of the buttons on the top. Example of Transacation Window after downlink and uplink is presented in the Figure 7.

5. Command-line Tooling

This chapter describes how to use the command-line tooling to generate FSDK code and projects. The CLI tooling is currently capable of generating new Component Types, Deployments and Libraries as well as generating source code and documentation for Component Types, Services, Libraries and Deployments. This section assumes some confidence in using the command line, see Section 3.3 for installation instructions.

5.1. Usage

The CLI program follows a common usage pattern:

$ codegen [codegen-type] [operation] [path] [options]In general the codegen command takes three positional arguments, followed by zero or more optional arguments. The first positional argument is the type of code generator you wish to use, the valid options are as follows:

componenttype, service, library or deploymentThe second positional argument is the operation you wish to perform on the code generator type:

-

generate: generate code and documentation -

generate-code: generates code only -

generate-docs: generates documentation only -

new: creates a new instance of the chosen type

The third positional argument is the target PATH and is relative to your current working directory. The PATH can be a full path to a target input xml, such as a componentType.xml or to the project folder e.g. path/to/MyDeployment/.

5.1.1. Optional Arguments Table

The following table lists all available optional arguments along with a brief description of what they do, for more detailed information you can look at the manual provided with GenerationOne by typing man codegen.

| Arg | Shorthand | Valid Codegen Types | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

--name |

-n |

componenttype, service |

The fully qualified name of the target unit type |

--unprotected |

-k |

componenttype |

Whether or not component type generates with protection lock |

--value-storage |

-s |

componenttype |

Whether or not component type generates with value storage |

--unit-tests |

-t |

componenttype |

Whether or not unit tests are generated |

--force |

-f |

any |

Force generation of all files, overwriting any files on disk |

--regenerate-all |

-a |

componenttype |

Regenerate all containers in a given directory |

--dry-run |

-d |

any |

Dry-run, shows files that would be generated without actually creating them |

--remove-unused |

-r |

deployment |

Clean files that will not be part of file generation list |

--board-specific |

-b |

componenttype, service, library |

Specifies the unit type is board specific |

--os-specific |

-o |

componenttype, service, library |

Specifies the unit type is operating system specific |

--build-config |

-c |

any |

Specifies the build configuration to use |

--help |

-h |

any |

Show command help information |

--verbose |

-v |

any |

Increase verbosity level |

--version |

N/A |

any |

Show version information |

5.2. Usage Examples

This subsection will cover how to use each of the code generator commands in more detail along with examples.

5.2.1. Component Types

The following command will generate a new Component Type xml in a library project:

$ codegen componenttype new my_library --name MyComponentTypeThere are multiple ways of generating existing Component Types. Platform independent Component Types can be generated by specifying the path to the componentType.xml or specifying the project and the fully qualified name of the Component Type.

This example uses the Dummy Component Type present in the app project.

$ codegen componenttype generate app/inc/Dummy

$ codegen componenttype generate app --name DummyIt is also possible to specify that a new Component Type should be platform specific by providing a build configuration along with whether the Component Type is board or operating system specific. The codegen tool will then look up the correct build configuration and extract the architecture information needed to generate. The following example shows how to generate the board specific RTC Component Type.

$ codegen componenttype generate framework/arch/csl_obc/inc/io/driver/RTC

$ codegen componenttype generate framework --name RTC --build-config csl_obc5.2.2. Services

Services are generated in a similar way to Component Types and are generally platform independent. Similar to Component Types, you can either specify the path to the service.xml or specify the project and the fully qualified name of the Service.

$ codegen service generate framework/inc/io/FSS

$ codegen service generate framework --name io.FSS5.2.3. Libraries

A new library project can also be created using the codegen tooling. New projects should be created in the root of the OBSW/Source directory. The following command will create a new library project called 'my_library'.

$ codegen library new my_libraryExisting library projects can be generated as follows:

$ codegen library generate my_library5.2.4. Deployments

A new deployment can also be created using the codegen tooling. New deployments should be created in the root of the OBSW/Source directory. The following command will create a new deployment called 'my_deployment'.

$ codegen deployment new my_deploymentTo generate code and documentation, including the Spacecraft Database for an existing deployment:

$ codegen deployment generate my_deploymentIt is also possible to simply regenerate the Spacecraft Database and documentation for a given deployment by specifying the

generate-docs operation.

$ codgen deployment generate-docs my_deploymentIf a deployment should be generated with a different build configuration to the default specified in the project.mk then

you may pass in a different build configuration.

$ codegen deployment generate my_deployment --build-config csl_obc6. Working with a Deployment

This section will take you through how to set up a GenerationOne FSDK deployment. It will show you the initial set up and then how to add new components to a deployment specification before then showing you how to generate code for that deployment and add in the initialisation data. The chapter will help take you through the different options that you will come across while working with an FSDK deployment.

The chapter will take you through the different parts of a deployment step by step. The final result is available in the gen1/OBSW/Source/legacy_tutorial1 directory.

6.1. Setting Up a New Deployment Project

To set up a project to create your deployment in, navigate to the OBSW/Source directory using the terminal, and execute the following codegen command:

$ codegen deployment new <name-of-deployment>This will generate a new project directory using the name you provided, containing all the files and directories necessary for creating your own deployment:

-

Makefile

-

config directory

-

project.mk

-

-

inc directory

-

src directory

-

deployment.xml

6.2. Deployment XML Model

The next step involves defining the deployment XML model within the deployment.xml file.

The deployment XML model follows a similar structure to the component XML, as you’ll find in the next chapter. It describes the structure of the deployment that you want to build, including what components to include as well as describing how various component instances connect to one another.

A good starting point for this is to reuse an existing model, and modify it to fit your needs. Copy the contents of the demo_linux deployment’s deloyment.xml file, and paste them within the deployment.xml file in your newly created project. Replace the name parameter in the Deployment section of the file with your project’s name and update any comments as required.

A large portion of the XML taken from the demo_linux project consists of setting up the communications stack. This is a list of connected components that describe how to collect and respond to telecommands and how to create and send telemetry. For the basic demo_linux deployment, we don’t need to add anything else to create a functional deployment. Similarly, the majority of the following tutorial doesn’t require any adjustments to the communications stack, although there is an extra section added as a reference point.

Similar to #includes in C, you need to identify the component types that are used in a deployment, and this is done in the import section. Unlike the deploy section that follows, the order in which components are imported is not important. For ease of navigation, we find it simplest to keep both lists in the same order.

Following the import section is the deploy section. This section defines both groups that are used in the deployment structure and each of the component instances in your deployment.

Before defining the component instances, component groups can be defined. It is not necessary to define every group used in a deployment, but defining a group allows for documentation to be added, which can help when searching for specific component instances.

After defining component groups, you define the component instances. The order in which the component instances are specified defines the order in which each instance is initialised. For each instance to be deployed, you need to describe the component type and then the name that you want to use to refer to that particular instance. In most cases, you may wish to name the instance the same as it’s component type. However being able to name different components allows you to give more meaningful names to components if you have multiple instances. We’ll come across such a case later on.

For this tutorial, we will start off by adding a simple component instance to the deployment’s XML. After that, we can move onto generating the deployment code and then filling out the initialisation data for this component before building the deployment and then interacting with the component through the TMTC Lab application.

The first component we’ll add is another dummy subsystem. A dummy subsystem component is a component that can be used for simple testing by holding parameters that can be set and retrieved.

To add a component to a deployment, you need to specify that it is to be used in the Import list, and then add it to the Deploy list. You’ll see that in the import list, Dummy is already being used. Scroll down in the Deploy section until you reach the component named 'platform.DummySubsys1'. Below this component, add a new one called 'platform.DummySubsys2'. The 'platform' before the name 'DummySubsys1' indicates to the code generation tool that the component instance should reside within the 'platform' component group. Component groups can be nested, for example 'cdh.tmtc.TMBeacon' would place the TMBeacon component instance into the cdh/tmtc/ group.

<Component name="platform.DummySubsys1" type="Dummy" />

<Component name="platform.DummySubsys2" type="Dummy" />As DummySubsys is a simple component, nothing more is needed to include the instance in the deployment. Once the XML is complete, the deployment code can be generated.

6.3. Generating a Deployment

6.3.1. Code Generation

To generate the deployment navigate to the OBSW/Source directory using the terminal, and execute the following codegen command, replacing <name-of-deployment> with your project name:

codegen deployment generate <name-of-deployment>This should have generated various new files and directories within the inc and src directories. Both directories now contain a deploy directory and an init directory. These are where deployment and initialisation data are handled respectively. There is also a deployment directory generated in src, this file provides the entry point for the deployment stage of the build system. The inc directory and src/deploy directory contain deployment generated code and should not be edited directly as they may accidentally be overwritten if the deployment is regenerated.

As with component generation (discussed in Section 8), there are files that are generated initially which can then be filled out by you. For deployments, these files are the initialisation source files located in src/init. If you change the group that a component instance is in, be sure to remove the old files (as they won’t be deleted) and to move/update the init file.

The next step after generating the deployment is to set up the initialisation data.

6.3.2. Component Initialisation Data

There are quite a number of components to initialise, most of which would require a more in depth understanding of the GenerationOne FSDK. To keep things simple for now, we will replace the generated initialisation source with the one from demo_linux. Simply copy and replace from demo_linux/src/init to your deployment project’s equivalent directory.

This should overwrite the duplicate files and leave just the additional dummy component to initialise. Using 'DummySubsys1' as a guide, fill out the initialisation data for 'DummySubsys2'.

With the initialisation data set, you can build and run your deployment.

6.3.3. Building a Deployment

Before attempting to build the deployment we first need to make sure the project.mk file is configured properly. Since we are building this deployment to run on a linux machine we need to specify this using the VALID_CONFIGS parameter. Assign VALID_CONFIGS the value linux, then save your changes. In addition, you will also want to make sure that the list of dependencies specified by DEPEND_DIRS is correct, according to the components you are including in your deployment. Since our deployment only contains components from the app and framework libraries, we can leave this as is. Once the project.mk file has been updated, we can build the deployment using similar steps to those for building a library (in Section 4.2.1). It should build without any errors. If there are errors, retrace the previous steps.

6.3.4. Building a Spacecraft Database

The Spacecraft Database is used to interact with a deployment using TMTC Lab, as seen in Section 4.2.8.

The Spacecraft Database is generated as part of a deployment generation step above, however it is possible to generate only the Spacecraft Database without generating deployment code. This is achieved using the codegen tool.

To generate the database standalone navigate to the OBSW/Source directory using the terminal, and execute the following command:

$ codegen deployment generate-docs <name-of-deployment>This generates a deployment.scdb file which it places within a directory named doc. This file will be used by TMTCLab to enable interaction with the spacecraft.

6.3.5. Interacting With a Deployment Using TMTCLab

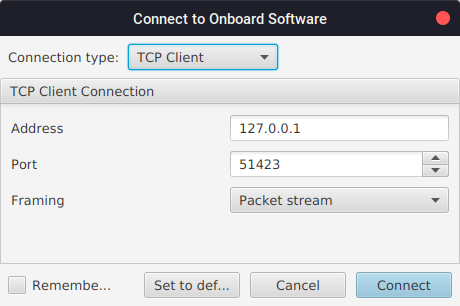

The deployment should be using a TCP client and so you’ll need to set the TCP server to connect to, which TMTC Lab can be used for. TMTC Lab can be run by executing the runLab.cmd script in the GNDSW/Source/TMTCLab/ directory. You should be greeted with a pop-up saying 'Connect to onboard software' followed by a TCP port. This is explained further in Section 9.2.3. The default settings should be valid so just click 'Connect'.

Now that the TCP server is running, you can run your deployment and interact with it. Since our deployment is built to run on linux we can simply run it directly from the terminal. To run the deployment navigate to OBSW/Source/<name-of-deployment>/bin/linux and execute the following command:

$ ./<name-of-deployment>You should see output in the console similar to below.

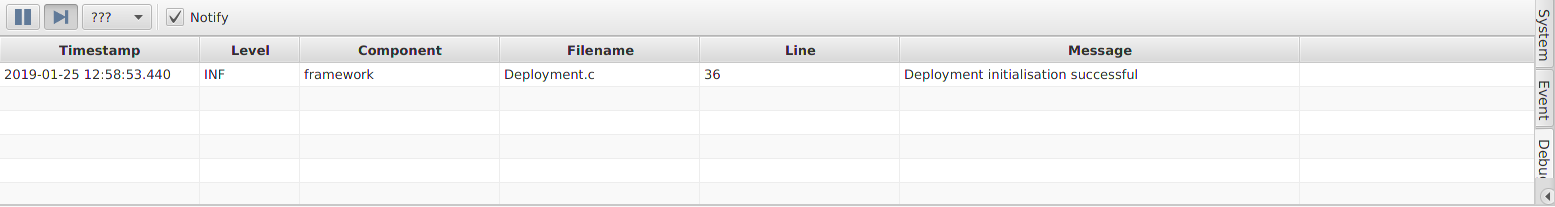

INF: arch/posix/src/Main.c:67 Platform initialisation successfulIn the Debug console window in TMTC Lab (Section 9.1.3.3) you should see that the deployment initialisation was also successful. Additionally, there may be some debug output regarding the deployment overwriting data, this is just the deployment setting up storage channels used by the loggers.

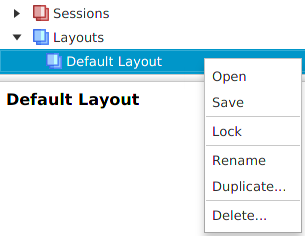

As mentioned previously, we’ll be interacting with the deployment using the generated spacecraft database. There is a section later on (Section 9.1.1) which goes into a more in depth view of using the Mission Explorer and TMTC Lab in general. For now, we’ll look at what we need to interact with the deployment.

-

Click 'File' → 'Manage deployments…'

-

Select the top row of the table, then click 'Set deployment…'

-

Set the 'Definition file' to be the

deployment.scdbfile you generated earlier. -

Click 'Open'

-

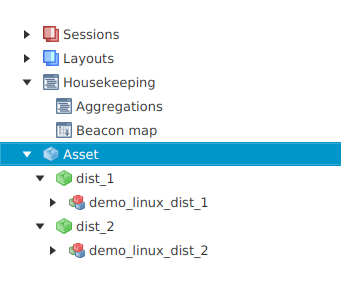

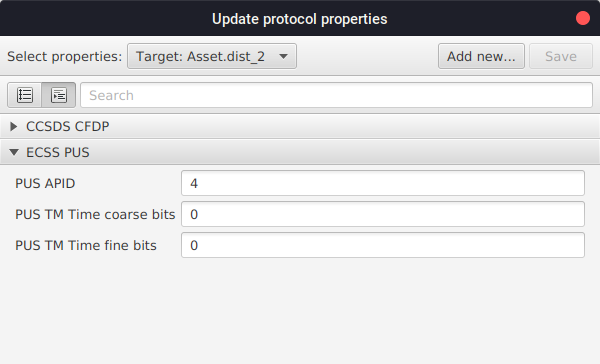

Close the 'Deployment Management' window. This should bring up the spacecraft database in the 'Mission Explorer' window on the left hand side of the GUI. Here, under your mission you’ll see a list of all the component groups with the component instances inside that you added to the deployment.

-

Open up the

platform.DummySubsys2component. You should see an action called 'Reset' and the three parameters that you set up in the initialisation data. -

Select one of the parameters and then press the 'Get' button that should have presented itself next to the list.

-

You should find that the hexadecimal value returned matches the one that you had set in the initialisation data. Click on letter 'H' to change values to decimal or binary numbers. The same will hold true for the other parameters.

-

You can also set the parameters which will change the stored value.

-

Finally, if you invoke the 'Reset' action, you should find that the parameters have returned to their initial values.

When you have finished using TMTC Lab, first disconnect the deployment (by stopping it from running) before disconnecting the packet server ('Connection' → 'Disconnect') to free up the TCP port.

6.4. Data Handling for Deployment Components

When you have a component in your deployment, you may wish to perform some data handling on the parameters that are accessible.

6.4.1. Adding to the Data Pool and Sampler

A common requirement of onboard software is to cache parameter data in a data pool. The GenerationOne FSDK provides the DataPool component to do this. A Sampler component is then used to periodically update particular parameters in the data pool. This is discussed in detail in Section 2.1.4.1 and Section 2.1.4.2.

Going back to the deployment.xml file, you should find that the DataPool component already has DummySubsys1 added to it. Add the DummySubsys2 component instance underneath the first one and give it a name to access it with (usually the same name as the instance).

Accessor defines will be generated for each parameter in the data pool. The individual parameters that we want to store in the datapool are specified here. It is possible to omit the parameter field, which will cause the datapool to generate parameters for each corresponding parameter for a component. We don’t want this for the Dummy component, because it’s dummyBuffer parameter has 65535 rows, which is a lot of data to cache, and unnecessary for this demonstration. As well as avoiding particularly large parameters, there may only be a few parameters which need to be pooled.

<Component name="cdh.DataPool" type="DataPool">

<ParameterAliases>

<ParameterBlock blockName="poolParameters">

<ComponentParameter name="DummySubsys1"

component="platform.DummySubsys1"

parameter="dummyParam8" />

<ComponentParameter name="DummySubsys1"

component="platform.DummySubsys1"

parameter="dummyParam16" />

<ComponentParameter name="DummySubsys1"

component="platform.DummySubsys1"

parameter="dummyParam32" />

<ComponentParameter name="DummySubsys2"

component="platform.DummySubsys2"

parameter="dummyParam8" />

<ComponentParameter name="DummySubsys2"

component="platform.DummySubsys2"

parameter="dummyParam16" />

<ComponentParameter name="DummySubsys2"

component="platform.DummySubsys2"

parameter="dummyParam32" />

</ParameterBlock>

</ParameterAliases>

</Component>6.4.1.1. DataPool LifeTime

While that will set up the DataPool component, there is also an optional connection to include an OBT component. Adding this time component will allow the DataPool component to determine whether pooled parameters can be considered expired, based on the DataPool’s lifeTime parameter. If it expires, then reading a pooled parameter will cause the DataPool to read through to update it’s value. To use this, add this before the ParameterAliases tag:

<Connections><Services>

<Service name="time" component="core.Time" service="time"/>

</Services></Connections>6.4.1.2. Setting up the Sampler

The Sampler component is already set up, it just needs to know which data pool parameters it should update. As the Sampler uses a periodic task, this also needs to be set up. Periodic tasks need three things to be set up:

-

the name of the task in the source,

-

which is found in the library documentation;

-

-

the period for the task in seconds,

-

which is currently set to 5 seconds;

-

-

and the priority for the task while running on the operating system.

Generate the deployment again and note that all but the src/init directory is updated. This stops you from accidentally overwriting extensive initialisation data that you may have set-up. Indeed, we don’t want to overwrite what’s already there, we’ll instead be adding to the initialisation data.

Open up DataPool_Deploy.h and you should find that some defines have been generated. As well as accessors for DummySubsys1 parameter aliases, there are now some for DummySubsys2 Now in BaseSampler_Init.c, add in these additional parameter defines to the array that currently contains DummySubsys1’s.

static const ui16_t gru16_BaseSamplerParamList[] =

{

DEPLOY_CDH_DATAPOOL_PARAM_ALIAS_INDEX_DUMMYSUBSYS1_DUMMY_PARAM32,

DEPLOY_CDH_DATAPOOL_PARAM_ALIAS_INDEX_DUMMYSUBSYS1_DUMMY_PARAM16,

DEPLOY_CDH_DATAPOOL_PARAM_ALIAS_INDEX_DUMMYSUBSYS1_DUMMY_PARAM8,

DEPLOY_CDH_DATAPOOL_PARAM_ALIAS_INDEX_DUMMYSUBSYS2_DUMMY_PARAM32,

DEPLOY_CDH_DATAPOOL_PARAM_ALIAS_INDEX_DUMMYSUBSYS2_DUMMY_PARAM16,

DEPLOY_CDH_DATAPOOL_PARAM_ALIAS_INDEX_DUMMYSUBSYS2_DUMMY_PARAM8,

};You can see from the sampler’s initialisation data that it will start off disabled and that its period multiplier is 10, which means it will run its task’s function every tenth call, and so approximately every 50 seconds.

In the spacecraft database explorer in TMTC Lab, enable the base sampler by setting the enabled parameter to 1. This will then start updating the DataPool. You can check this by changing one of the platfom.DummySubsys2 parameters.

6.4.2. Logging and Monitoring Parameters

Another common data handling requirement is to periodically log parameters, through the use of a data logger and also to monitor parameter values, to check that they’re in range. This next tutorial section will take you through how to add a parameter to the base aggregator so that it is logged along with other aggregated data and also how to set up a monitor on a parameter.

6.4.2.1. Adding to an Aggregator for Logging

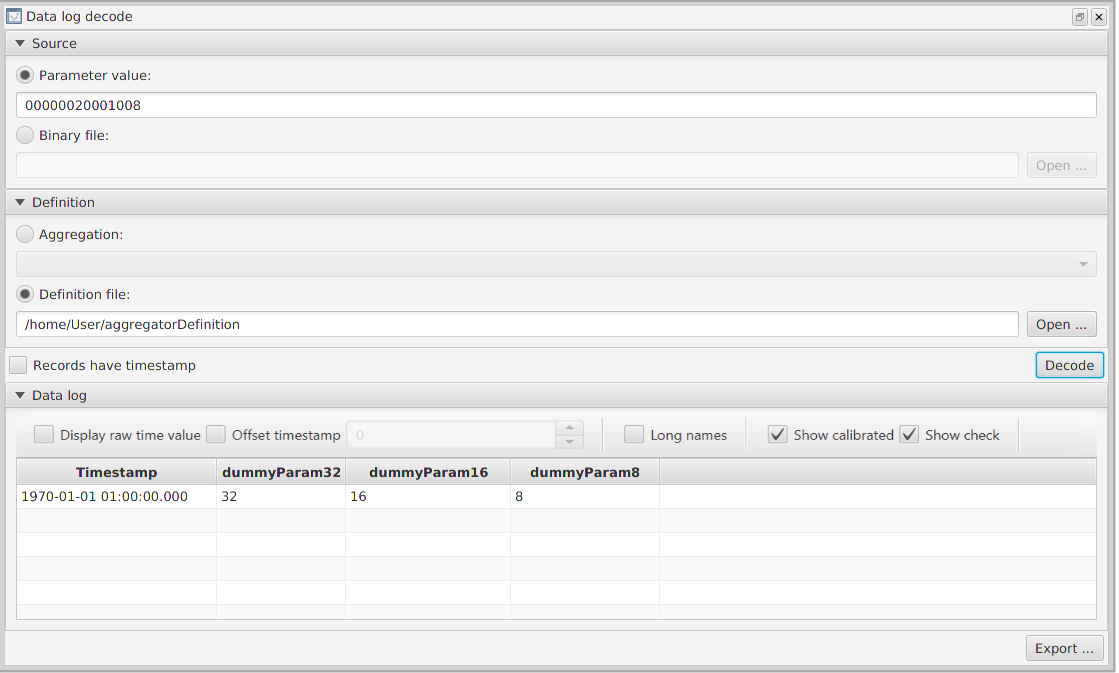

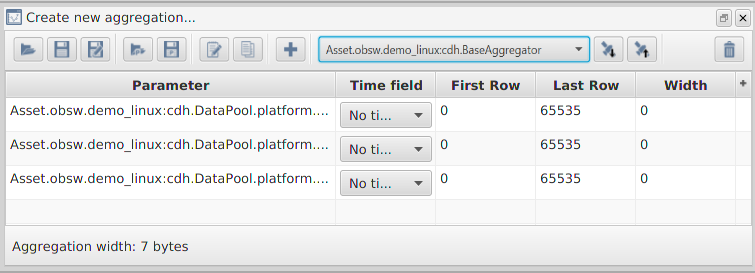

DataLoggers periodically store a given parameter in a specified data channel. To store multiple parameters, aggregators are used to bit-pack provided parameters into a compact state for logging. The initialisation data for aggregators is similar to that of the other data handling components, and can be edited manually to modify the parameters in the aggregation. There is also the possibility to use the graphical aggregation builder in TMTC Lab to define and modify aggregations, in which case the deployment generation step will create the aggregator initialisation data for you.

As demo_linux uses automatically-generated aggregator definitions, we will first run through the process using TMTC Lab.

-

Generate the latest spacecraft database

-

Open up the spacecraft data in TMTC Lab

-

Launch the aggregation builder by selecting 'Tools' → 'Aggregation builder…'

-

Select the toolbar button for loading a portable definition (a folder with a 'P' on it)

-

Browse to the location of the

demo_linuxdeployment project and into thedefdirectory -

Select the

BaseAggregator.yamlfile and click 'Open'. This will bring up the configuration for the BaseAggregator in the aggregation builder. -

Add

DummySubsys2’spooled parameters by locating them in the main spacecraft tree on the left and dragging them into the aggreation builder, do this with all three of theDummySubsys2pooled parameters to give a total of six parameters. -

You will see that the 'Last Row' for the

DummySubsys1parameters is the value '65535'. This is treated as a special value to indicate that the aggregator should use as many rows as there are available. Set the 'Last Row' on the parameters you just added to '65535'. -

Save the aggregation in portable form (the disk icon with a 'P' on it), overwriting the existing definition.

-

Regenerate the deployment. You should be able to look at the initialisation data in

src/init/cdh/BaseAggregator_Init.cand verify that the new parameters have been added.

Without a YAML file with the same name as the aggregator component in the `def} directory, the initialisation data for the aggregator will not be generated by the deployment code generator. In this case the file can, and should, be edit manually. The equivalent manual process for the steps we went through above is as follows:

-

Open up

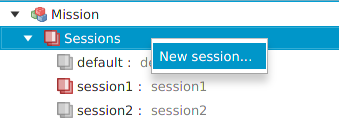

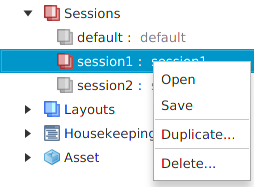

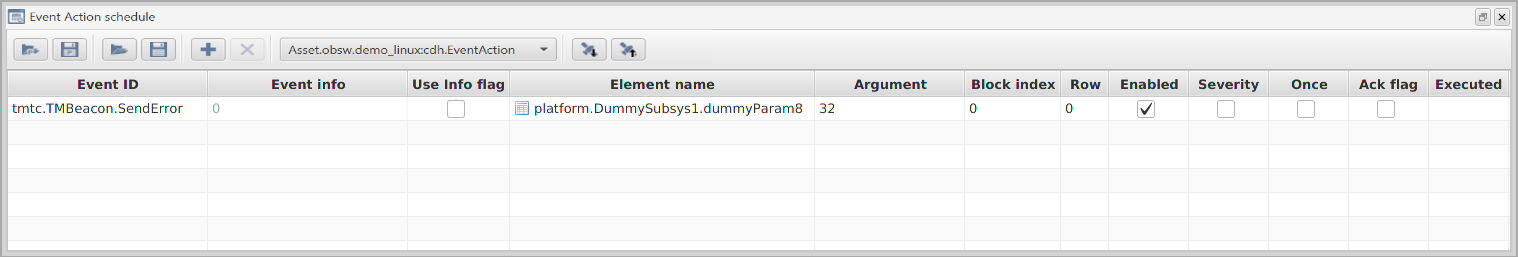

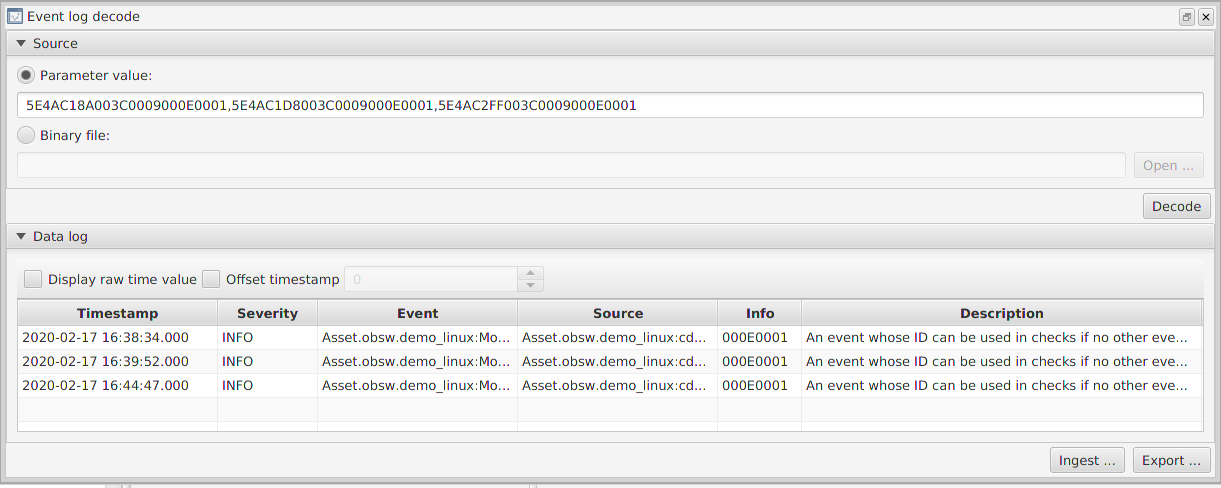

src/init/cdh/BaseAggregator_Init.c.-